Three young players from Xinjiang are taking root in the national team.

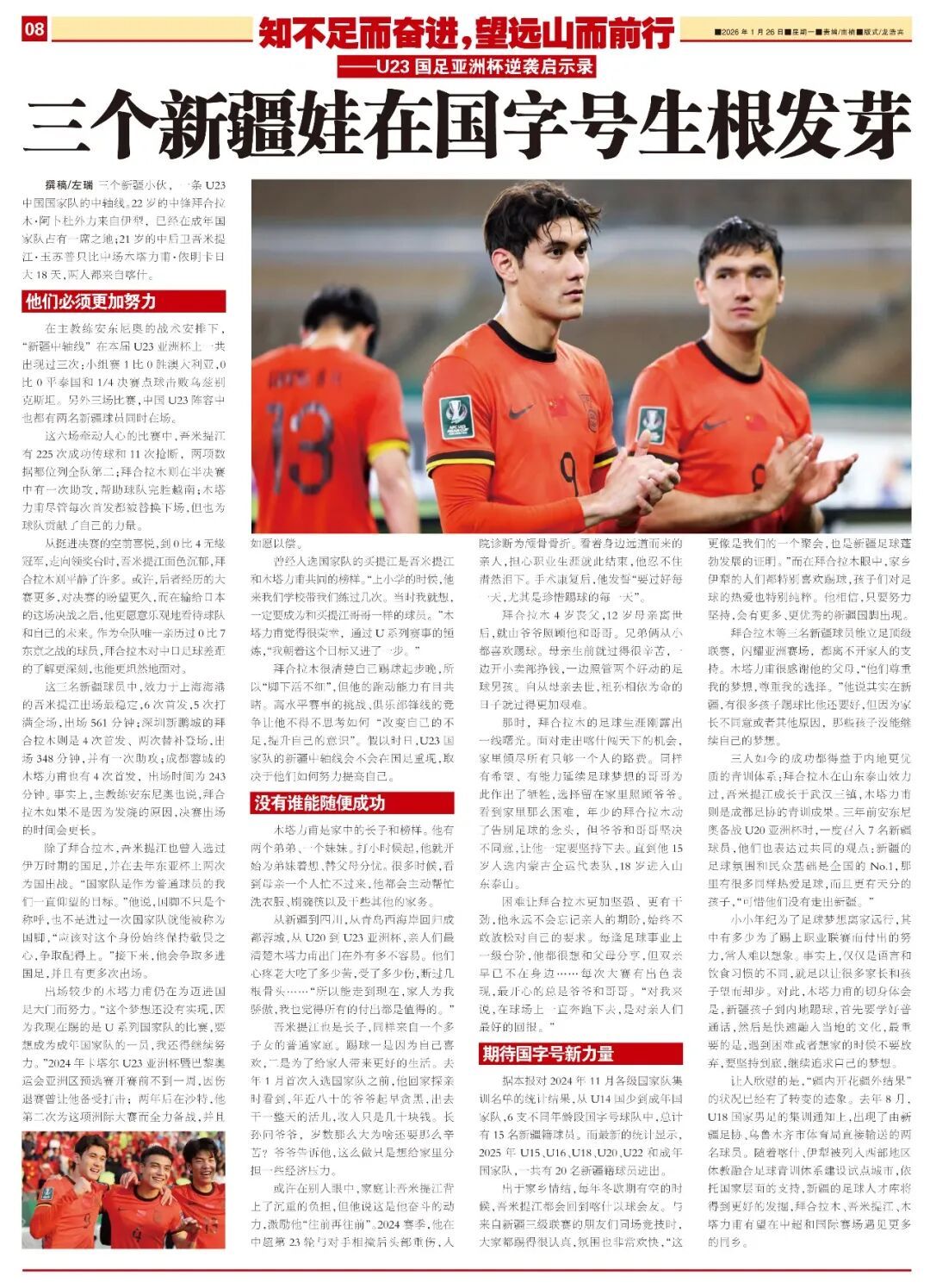

Written by Zuo Rui Three young men from Xinjiang coincidentally cover the defensive, midfield, and attacking lines of the U23 national team: 22-year-old striker Baihalamu Abduwali from Ili has previously earned a place in the senior national squad; 21-year-old center-back Wumitijiang Yusupu is just 18 days older than midfielder Mutalifu Yimingkar, both hailing from Kashgar.

Under head coach Antonio’s tactical plan, the "Xinjiang central axis" appeared three times during this U23 Asian Cup: a 1-0 group stage win over Australia, a 0-0 draw with Thailand, and a penalty shootout victory against Uzbekistan in the quarterfinals. In the other three matches, the China U23 lineup also featured two Xinjiang players on the field simultaneously.

Across these six gripping matches, Wumitijiang completed 225 successful passes and made 11 interceptions, ranking second in both categories on the team; Baihalamu provided an assist in the semifinal, helping the team to a comprehensive win over Vietnam; although Mutalifu was substituted off in every start, he still contributed his share to the team.

From the unprecedented joy of reaching the final to the 0-4 loss that denied them the championship, Wumitijiang showed a somber expression on the podium, while Baihalamu appeared much calmer. Perhaps having experienced more major tournaments and awaited the final for longer, Baihalamu is more optimistic about the future of the team and himself after the defeat to Japan. As the only player on the team who witnessed the 0-7 Tokyo match, Baihalamu has a deeper understanding of the gap between Chinese and Japanese football and can face it more calmly.

Among the three Xinjiang players, Wumitijiang, who plays for Shanghai Port, had the most consistent appearances with 6 starts and 5 full matches, totaling 561 minutes; Baihalamu from Shenzhen New Pengcheng started 4 times and came on twice as a substitute, playing 348 minutes with one assist; Mutalifu from Chengdu Rongcheng started 4 times, accumulating 243 minutes. In fact, coach Antonio mentioned that if Baihalamu had not been sick with a fever, he would have played more in the final.

Besides Baihalamu, Wumitijiang was also selected during Ivan’s tenure for the senior national team and played twice in last year’s East Asian Cup. “The national team has always been a goal we ordinary players look up to,” he said. Being a national team player is more than just a title or a single appearance; one should always respect this identity and strive to deserve it. Moving forward, he aims to earn more call-ups and play more matches for the national team.

Mutalifu, who has fewer appearances, is still working hard to enter the senior national team. “This dream is not yet realized because I’m currently playing for the U-series national teams. To join the senior national team, I have to keep pushing myself.” Less than a week before the 2024 Qatar U23 Asian Cup and Paris Olympic qualifiers in Asia, he had to withdraw due to injury, which was a heavy blow; two years later in Saudi Arabia, he prepared fully again for this continental competition and finally achieved his goal.

Former national team member Maitijiang is a shared role model for Wumitijiang and Mutalifu. “When I was in elementary school, he came to our school to train us several times. At that time, I thought I must become a player like Brother Maitijiang.” Mutalifu feels honored and believes that through the U-series competitions, “I have taken another step toward this goal.”

Baihalamu is well aware that he started playing football late, so his ball control is not very refined, but his running ability is widely recognized. The challenges of high-level competitions and competition for forward positions at his club force him to think about how to “improve his weaknesses and enhance his game awareness.” In time, whether the Xinjiang central axis of the U23 team will reappear in the senior national team depends on how much they improve themselves.

Mutalifu is the eldest son and a role model in his family. He has two younger brothers and a sister. From a young age, he has cared for his siblings and helped ease his parents’ burdens. Often, when he sees his mother overwhelmed, he voluntarily helps with laundry, washing dishes, and other household chores.

From Xinjiang to Sichuan, returning from Qingdao West Coast to Chengdu Rongcheng, and from U20 to the U23 Asian Cup, his family knows how tough it has been for Mutalifu to be away from home. They feel sorry for how much hardship he has endured, how many injuries he suffered, and how many bones he has broken… “So reaching this point makes my family proud, and I believe all the effort has been worthwhile.”

Wumitijiang, also the eldest son, comes from a regular family with multiple children. He plays football partly because he enjoys it and partly to provide a better life for his family. Before his first national team call-up in January last year, during a home visit, he saw his nearly eighty-year-old grandfather working from dawn to dusk for just a few dozen yuan. When he asked why his grandfather worked so hard at that age, his grandfather said it was to ease the family’s financial burden.

To others, family might seem like a heavy burden for Wumitijiang, but he says it is his motivation to keep pushing forward. In the 23rd round of the 2024 Chinese Super League season, he suffered a severe head injury after a collision, diagnosed as a skull fracture. Seeing relatives travel far to visit and fearing his career might be over, he couldn’t hold back tears. After surgery and recovery, he vowed “to live well every day, especially to cherish every day I can play football.”

Baihalamu lost his father at age 4 and his mother at 12, after which his grandfather took care of him and his brother. Both brothers loved football from a young age. Their mother struggled hard during her lifetime, running a small shop while looking after two lively football-loving boys. Since her passing, life for the grandfather and grandsons has become even tougher.

At that time, Baihalamu’s football career was just beginning to show promise. Facing the opportunity to leave Kashgar and pursue his dream, the family could only afford one person’s travel expenses. His equally hopeful and capable older brother sacrificed his chance and stayed home to care for their grandfather. Seeing the family’s difficulties, young Baihalamu once considered quitting football, but his grandfather and brother firmly opposed this and urged him to persevere. Eventually, at 15 he was selected for the Inner Mongolia Provincial Games team and at 18 joined Shandong Taishan.

Hardship made Baihalamu stronger and more determined. He never forgets his family’s expectations and never relaxes his self-discipline. Whenever he reaches a new milestone in football, he wishes he could share it with his parents who are no longer with him… After every outstanding performance in major tournaments, his grandfather and brother are always the happiest. “For me, running on the pitch continuously is the best way to repay my family.”

According to this newspaper’s statistics on the 2024 November national team training rosters, from U14 youth teams to the senior national team, there are 15 Xinjiang-born players across six different age-group national teams. The latest data shows that in 2025, a total of 20 Xinjiang players are involved in the U15, U16, U18, U20, U22, and senior national teams.

Out of hometown affection, Wumitijiang returns to Kashgar during winter breaks to play football and socialize. When competing with friends from Xinjiang’s third-tier league, everyone plays seriously and enjoys a lively atmosphere. “It’s more like a gathering and also proof of the flourishing football scene in Xinjiang.” Baihalamu observes that people in his hometown Ili love football deeply, and children’s passion for the sport is very pure. He believes that with effort and persistence, more and better Xinjiang national players will emerge.

The success of Baihalamu and the other two Xinjiang players in top-tier leagues and on the Asian stage owes much to family support. Mutalifu is very grateful to his parents, “They respect my dream and my choices.” He says many kids in Xinjiang play football better than him, but due to parental disapproval or other reasons, those children couldn’t continue pursuing their dreams.

Their current achievements benefit from the superior youth training systems in mainland China: Baihalamu played for Shandong Taishan, Wumitijiang developed at Wuhan Three Towns, and Mutalifu is a product of Chengdu Football Association’s youth program. When coach Antonio prepared for the U20 Asian Cup three years ago, he called up seven Xinjiang players, who shared a common view: Xinjiang’s football atmosphere and grassroots support are the best in the country, with many talented and passionate kids, “but unfortunately, they haven’t left Xinjiang.”

At a young age, many leave home to chase their football dreams, making efforts to reach professional leagues that are hard for most to imagine. Even differences in language and diet can discourage many parents and children. From his own experience, Mutalifu says Xinjiang kids playing in the mainland must first master Mandarin, then quickly adapt to local culture, and most importantly, never give up when facing difficulties or homesickness, but persist to realize their dreams.

Encouragingly, the situation where Xinjiang’s talent blooms locally but bears fruit elsewhere is beginning to change. In August last year, the U18 national men’s team training roster included two players directly sent by the Xinjiang Football Association and Urumqi Sports Bureau. With Kashgar and Ili designated as pilot cities for the integration of sports and education football youth training system in western China, supported at the national level, Xinjiang’s football talent pool will be better developed, and Baihalamu, Wumitijiang, and Mutalifu are expected to meet more fellow Xinjiang players in the Chinese Super League and international competitions.

Wonderfulshortvideo

The footwork, the finish 🤌

Did you get it? 🤔😅

The Wirtz x Sané link-up 🔗

Haaland’s movement 🥵

Which counterattack is

When you use your girlfriends shower 🚿 @Emily Bourne @LUSH

🤤🤤

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App