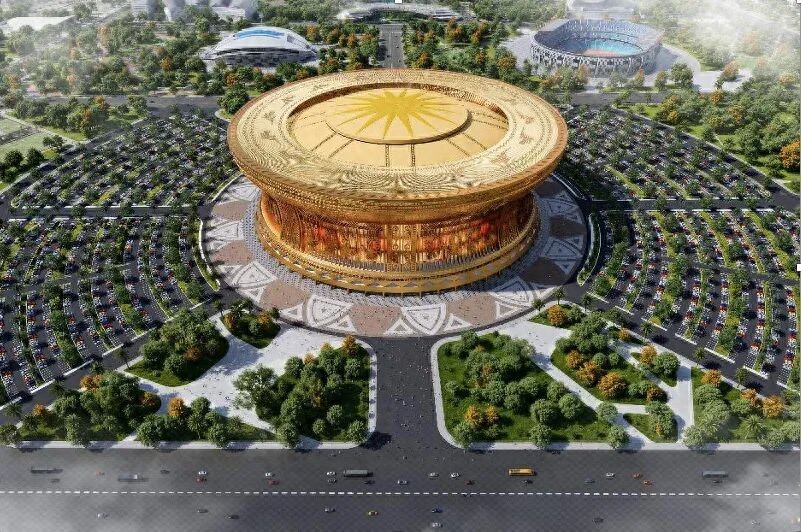

Building the world's largest stadium: Can this mega project help elevate Vietnamese football?

By Han Bing Where is the world’s largest stadium by capacity? At present, it is in India, but by 2028, Vietnam may claim this title—this week, leading Western sports outlets have widely covered Vietnam’s construction of the "Dong Drum" stadium in southern Hanoi, designed to accommodate 135,000 people, exceeding Ryugyong Stadium (Pyongyang, North Korea, 113,000), Hassan II Stadium (Casablanca, Morocco, 115,000), and Modi Stadium (Ahmedabad, India, 132,000).

Vietnamese football has grown rapidly in recent years, but currently only Hanoi’s My Dinh Stadium (40,000 capacity) meets FIFA standards. With a population of 100 million, Vietnam’s national sports strategy aims to host major events like the Asian Games, Olympics, Asian Cup, and World Cup. Building a large-scale, modern football and multi-sport complex is urgent, and having the world’s largest stadium clearly reflects Vietnam’s sporting ambitions.

The Dong Drum Stadium, whose construction began late last year and is named after the traditional Đông Sơn bronze drum, features a giant retractable roof, fully air-conditioned interiors, and artificial intelligence technology, all designed to be state-of-the-art. With a capacity of 135,000, it will not only offer an advantage in hosting large football, sports, and entertainment events but also become a new world-class landmark in Asian sports, significantly boosting Vietnam’s international profile.

Besides Dong Drum Stadium, Vietnam is building two other stadiums: the PVF Stadium in the north, which broke ground last October with a 60,000 capacity, and Ho Chi Minh City’s Lich Chi Stadium, started this January with a 75,000 capacity. The latter is also the National Sports Center, with a total investment of $5 billion. The Olympic Sports City, where Dong Drum is located, costs $35 billion and is funded by Vin Group, owned by Vietnam’s richest man Pham Nhat Vuong. However, with a national GDP around $500 billion, such massive investment in large sports facilities poses huge challenges in funding, technology, and construction.

Lich Chi Stadium

PVF Stadium

Moreover, even if completed on schedule, attendance and utilization rates remain concerns. With three super-large stadiums totaling 270,000 seats, the Vietnamese national team only attracts over 40,000 spectators for major matches. The average attendance for the Vietnamese league is about 5,000, with a season high of just 14,000 this year. Even if football clubs occupy all three stadiums, matchday revenue and daily operations will face enormous profitability pressures.

Globally, there are many examples of poorly planned "mega stadiums" built excessively large. The Stadio San Nicola, built for the 1990 World Cup with a 60,000 capacity in Bari, Italy’s ninth-largest city, has seen only two Serie A seasons in 20 years, averaging 10,000 spectators per game, making maintenance a heavy burden on the city budget. Brazil’s capital stadium, Estádio Mané Garrincha, constructed for the 2014 World Cup, lacks a permanent top-tier club tenant and sees less than 1% attendance on most matchdays. During the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, it was even used as a bus parking lot, with annual maintenance costs reaching $10-15 million.

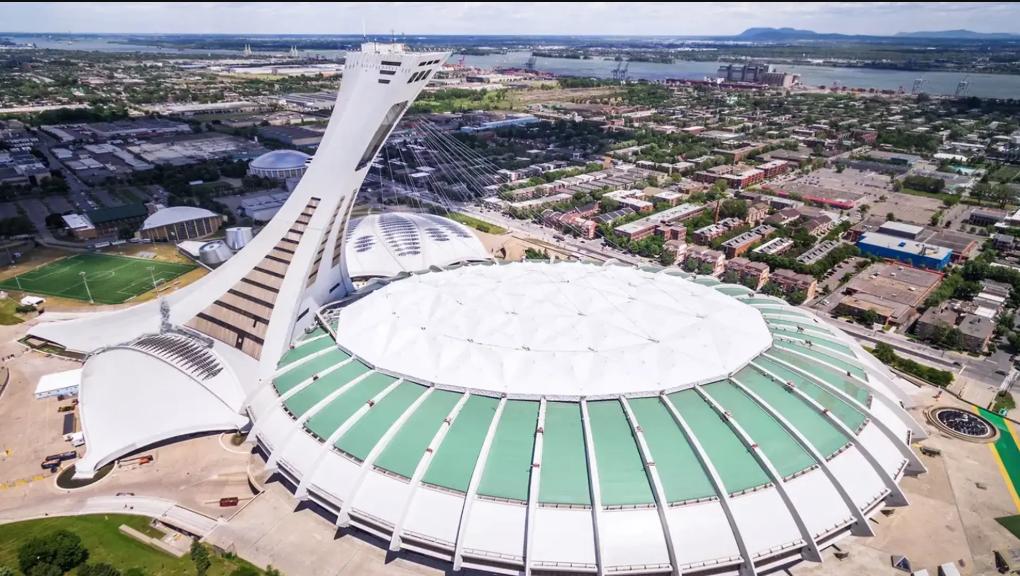

Montreal Stadium

The most notorious failed large sports venue is Montreal’s Olympic Stadium, built for the 1976 Olympics. Initially costing 134 million CAD, it was rushed into use unfinished, with costs ballooning to 1.1 billion CAD. The debt was only fully paid off 30 years later, in 2006. By then, maintenance costs had reached 1.66 billion CAD (about $4 billion today). Since 2004, no permanent sports teams have called it home. Its retractable roof was completed over a decade after opening; design flaws caused wind speeds over 40 km/h to prevent proper operation. The roof opened only 88 times total, with each operation costing $45 million.

For an ambitious nation like Vietnam aiming to become a football and sports powerhouse, launching a mega project centered on the world’s largest stadium may seem like a step too far to outsiders.

Wonderfulshortvideo

Did you get it? 🤔😅

Haaland’s movement 🥵

When you use your girlfriends shower 🚿 @Emily Bourne @LUSH

Neymar highlights neymar edit neymar lamine yamal celebration

Arsenal 1-0 chelsea havertz goal

yamal goal yamal instagram yamal dribble barcelona 2-1 albacete yamal highlights yamal edit

casemiro goal casemiro assist casemiro 6 7 celebration

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App